Like many English teachers, I’m a little preoccupied with the craft of writing. I am always nudging my students to think about how an author wrote something before they start gabbing about what the piece was about.

The challenge to these conversations is that they can feel a bit dry. Why look at narrative structure or sentence variation when we could be dissecting the juicy points of the plot? As a result, discussion of craft was something I would squeeze in here and there, but it was only last year that I decided to devote a whole unit and benchmark project to the concept.

Essential Questions:

- What systems do I use in my own writing?

- What impact does writing style have on the reader?

- How can we emulate the writers we love?

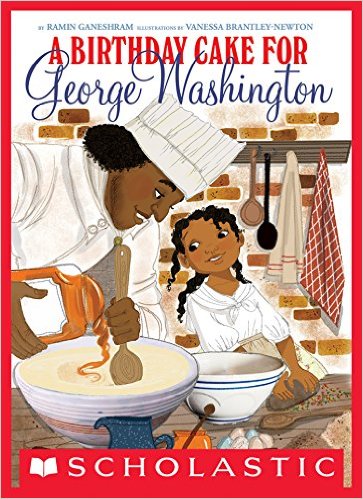

My bright idea was that students would pull from their independent reading to create a kind of handbook. First, they would learn the basic terminology and concepts of writing style, and then use those to analyze selections from their own books. Finally, they would write a miniature scene (300 words or so) of their own, seeking to emulate the author’s style they had just dissected.

This is a good example of a project that I had to try doing myself, at least partially, before I could ask my sophomores to try it. We used the online layout app Lucid Press, and I created both a blank template and a Partially filled out version.

Here’s a few examples of projects that met or exceeded expectations:

What Makes This Unit Work?

Letting students explore an independent reading book puts them in the driver’s seat — it’s on them to pick something they would like to spend a couple weeks dissecting.

I also emphasize the difference between emulation and copying. When it comes to creative expression, studying the style of others is how we define our own, whether it’s our clothes, our music, or our writing. Professional authors spend a ton of time thinking about the how in addition to the what, so we should all practice that.

I also asked students to do an “About the Authors” page where they included info about themselves alongside the author they chose to emulate. These are as fun to read as you are hopefully imagining.

Lastly, I made it a requirement that students reach out to the author they emulated to share their work, whether it was via Twitter or an email to their publisher. There were a bunch of automated responses, but a few personal ones as well. The process of sharing definitely made the students nervous, in a good way.

Oh — and after the gallery day of reading each other’s projects, they had to use somebody else’s handbook to overhaul their short writing piece. Trying to turn a piece of writing that was originally supposed to sound like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie into something that sounds like Orson Scott Card? Weird, fun, in the spirit of Mad Libs but with actual skill involved.

Here’s the UbD unit plan with a sketch of the daily timeline, as well as the project instructions and rubirc.

This past summer, I got an email inviting me to write about what it’s like to work in a school that doesn’t really believe in standardized tests… but still has to administer them.

This past summer, I got an email inviting me to write about what it’s like to work in a school that doesn’t really believe in standardized tests… but still has to administer them.